Newsletter – 2nd

August 2022

Researchers make their own luck

Save 20% on Findmypast.com.au subscriptions

Ancestry launch Chromosome Painter

Using settlement certificates in family history research

A technologically-challenged

grandmother writes….

Gene therapy that might

have saved the Romanovs

Somerton Man identified

after 74 years?

Review: Marriage Law for Genealogists

The LostCousins

newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue

(dated 19th July) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between

this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February

2009, so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main

LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not

already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you

whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

Researchers make their own luck

There’s

an old saying, often attributed to Gary Player – or fellow golfer Arnold Palmer

– though neither of them was the first to use it. There are several variations,

but they’re all on the same theme: “The more I practice the luckier I get.”

It’s

the same for researchers, from Archaeologists to Zoologists, and everyone in

between – including family historians. This recent blog

post by professional genealogist Clare Kirk is a wonderful example of what we

can achieve, if we only try – it’s an incredible story, and just what I’d expect

from a LostCousins member!

Save 20% on Findmypast.com.au

subscriptions

It’s

National Family History Month in Australia and New Zealand, so Findmypast are

marking the occasion with a discount on all of their subscriptions – though as

the discount only applies to the first payment, you’ll make by far the biggest saving

when you lock in the discount for a full year with a 12 month subscription.

20%

discount reduces the cost of a 12 month Plus subscription to $185.59, whilst a

Pro subscription – which includes newspapers and worldwide records – costs $256.79.

To support LostCousins please follow the link below and if you get a message

about cookies click That’s fine (you can always go back and change the

settings later):

Findmypast.com.au

– SAVE 20% ON ALL SUBSCRIPTIONS

Note:

in the USA Family History Month is October, but that doesn’t necessarily mean

there will be an offer from Findmypast then (not least because Black Friday will

be just around the corner).

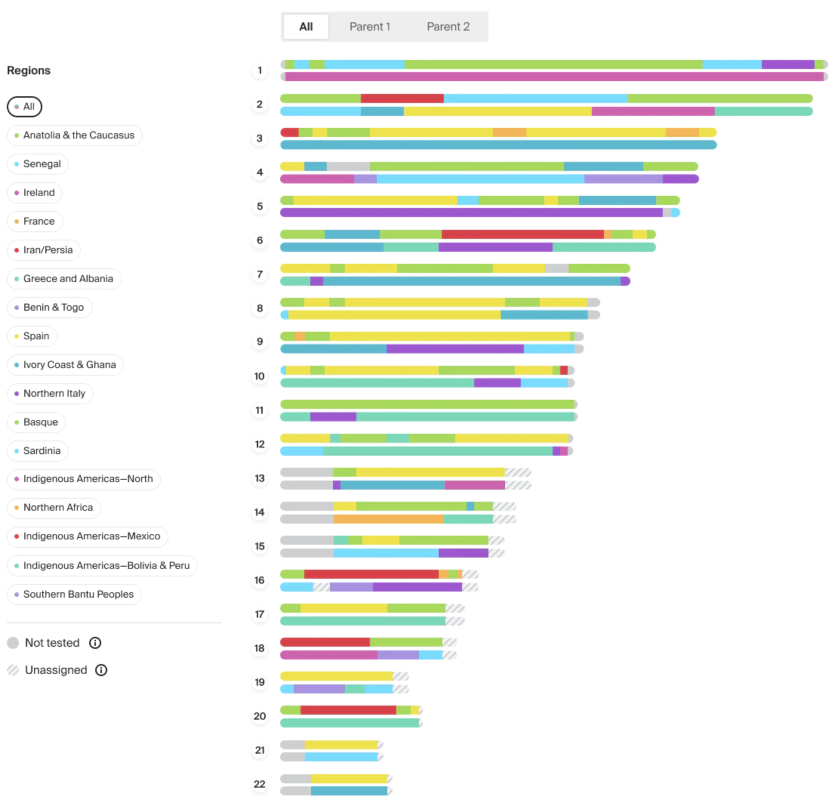

Ancestry launch Chromosome

Painter

Earlier

this year Ancestry announced their new SideViewTM technology, which

uses sophisticated algorithms to identify which parts of a user’s DNA came from

each parent – you can re-read my newsletter article here,

but it’s also worth taking a look at Ancestry’s press release, which you may not have seen

at the time.

For

me, the key sentence in that press release was this one: “SideView™

technology groups matches with a precision rate of 95% for 90% of AncestryDNA

customers thanks to the size and statistical power of the AncestryDNA match

network”

Those

95% and 90% figures look impressive, but when you start looking at individual

chromosomes a 5% error rate could mean that one or two chromosomes have been

allocated to the wrong parent – and whilst this may not be obvious in cases

where both parents have similar ancestry, in other circumstances it could cause

confusion. There’s also the possibility that you’re in the 10% minority for

whom the error rate is higher.

Ancestry

have now followed up with the release of their Chromosome Painter which, in

effect, shows the workings behind your ethnicity estimate. You can read about

this new feature on Ancestry’s Support page

– though the example shown there, and reproduced below, looks nothing like my

results, which are far less interesting!

Remember

that Ancestry don’t tell you which of your parents is Parent 1, and which

Parent 2 – that’s something you need to figure out based on your knowledge of

their ancestry.

If

you are fortunate enough to have been able to test one or both parents (as well

as yourself), I’d be interested to know what you make of the Chromosome

Painter, which you can access by going to the Ethnicity Inheritance

block in your DNA Story, then clicking View breakdown. But don’t

write to me, please instead post your comments on the LostCousins Forum in this

discussion.

If you have access to multiple test results note that you can only see this information

for your own test, and any other tests where you have been appointed Manager.

Tip:

you don’t need to be a member of the forum to see most of the information

posted there, but you do need to be a member if you want to post a contribution

of your own. Most of the people who read this newsletter have already been invited

to join the forum, or could easily qualify by adding a few more relatives to

their My Ancestors page (something that they probably ought to do anyway!). See

your My Summary page to find out whether you’ve already qualified, or how far

you’ve got to go – you need a Match Potential of 1 or more, and you can make up

the shortfall most quickly by entering relatives from the 1881 censuses.

In

the latest issue of The Journal of Legal History Professor Rebecca Probert

writes about ‘civil marriage’ in the context of the 1836 Marriage Act – you can

download the PDF here (it’s

one of several articles in the issue which are open access). If you haven’t yet

read Professor Probert’s latest book (see review below) it’ll underline just

how complex marriage law and marriage practice can be!

Note:

on the Subscribers Only page at the LostCousins site you’ll find a link to a talk

that Professor Probert gave to LostCousins members earlier this year.

Using settlement certificates

in family history research

I’m

delighted to be able to publish this article, by an expert in the field, on a valuable

resource that is all too often forgotten about….

Most

family historians are familiar with using census material, and many will have

visited a record office to look through parish registers of births, marriages

and deaths. A relative few however will have attempted to look at settlement

certificates. This is not really surprising, since they were not required of

all the population in the same way as registrations, their survival rate is

very patchy, and most are not available online at sites such as Ancestry or Findmypast.

Nonetheless,

such certificates can be very informative if you are able to track one down from

your family’s past. As with all sources though, care should be taken in

understanding what they are really telling you.

What were settlement

certificates?

Settlement

certificates became mandatory after 1697, when the Act for the Better Relief of the Poor laid down that a person

moving from one parish to another, if they were to be renting a property worth

less than £10 a year, had to have a certificate from their parish of origin

saying that they would pay for any relief the person may need if they fell on

hard times.

Note:

Many sources cite the 1662 Settlement Act as the introduction of settlement

certificates – this is erroneous. A form of settlement certificate grew up

after 1662, but these were technically bonds between one parish and another,

underwritten by local worthies normally to an amount of about £40.

Without

such a certificate a person could be moved on at the behest of the overseers

and magistrates of the destination parish. With it the person was safe unless

they claimed for relief.

At

the time of the passage of the Act, and for most of the following century, this

covered the majority of the population. You had to be quite comfortably wealthy

in order to avoid needing a certificate. Their use continued until they were

officially abolished in the 1865 Union

Chargeability Act, which made Unions, not parishes, responsible for raising

rates. In practice their use had started to fade long before this, and not many

collections go on much after 1834. Consequently their use covers about 150

years, and the record offices of the country contain tens of thousands of them.

The

problem is searching them. A lot of record offices have calendared their

settlement and removal certificates, and they are available on CD ROMs, which

themselves are indexed by name. Some record offices even have a name search

available on their catalogue, which will bring up the appropriate certificate.

If you have a family name associated with a particular county in the eighteenth

century, and can with reasonable certainty associate them with a parish or

borough (through registry material) you may well be in luck.

Supposing

you do manage to track down such a certificate from your family’s tree. What

can it tell you?

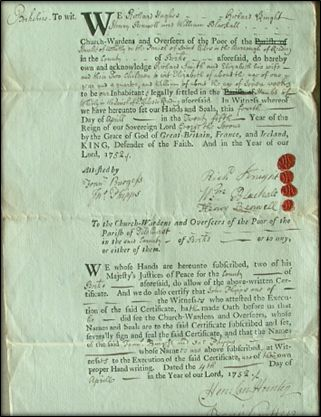

Most

settlement certificates look like this:

Figure

1:

Berkshire Record Office D/P 96/13 (used by kind permission of Berkshire Record

Office); this and many other interesting documents can be found on the CD ROM Berkshire

Overseers’ Papers compiled by Berkshire Family History Society and Berkshire

Record Society, and available from the Berkshire FHS shop.

It

gives you the name of the settler, normally a man, and usually the name of his

wife, and the names and ages of his children. It will be written by the

overseers of the poor in one parish to the overseers of the poor in another

parish. There will be a date, and sometimes a profession for the settler. There

is also a provision for a signature, but more often, especially early in the eighteenth

century, this is only a mark. They are proof of movement of this family from

one place to another.

One

significant misreading of settlement certificates is that they give the date of

a person’s migration from one parish to another. This is rarely the case.

What

the date on a settlement certificate actually does signify is still a matter

for debate, but most are in agreement that settlers did not habitually get a

certificate from their parish of origin as they left. Sometimes they did, and

this is often shown by an address to the destination parish such as “to whom it

may concern” or “the overseers of the parish of St. Mary’s or St. Andrews in

Anytown”. Most accept that certificates were sent for once a person had settled

in a parish; often if they got married in the destination parish. This was

because a parish might accept a single man looking for work without question,

but once he was likely to produce hungry offspring they wanted the insurance of

a host parish. If you are lucky you may

well find a settlement certificate around the date of your ancestor’s marriage.

Sometimes the certificates could be in response to the family falling on hard

times, often after the birth of yet another baby, a lot of certificates have

very new born babies on them. If they presented to the parish looking for

relief the likelihood is that the parish would examine them to establish where

they were settled, and then send to the overseers of that parish for a

certificate, and an agreement to pay up. If they didn’t they could be removed.

In

some parishes, like the ones I have studied in Reading, a bunch of certificates

were issued all in one go, around the same time that the poor rates start going

up. This is good housekeeping on the part of the parish in difficult times.

They are making sure they know who is going to pay for their settlers in the

event of the need for relief. It does not mean that the settlers have applied

for relief.

If

you do find a settlement certificate, then you could well be on threshold of a

treasury of information about your family. It is worth searching then under

“examinations” to find out if there is an examination associated with the

certificate. This could be in the parish of origin, but is most likely in the

host parish, and would have been carried out by the JPs. This will give a huge

amount of information, where the man has worked all his life, what he has been

paid, properties rented, all his marriages and relationships, apprenticeships,

parish positions, where he has paid rates, times in prison, in the armed forces

and any amount more. It may also be worth looking at “removals”, to see if the

unfortunate family were sent back to where they came from. The last source

associated with this is a possible appeal at the Quarter Sessions. If you find

a removal, then the chances are that the origin parish appealed, which means

there will be a case in the County Quarter Session minutes from around the time

of the removal.

Settlement

certificates are a real jewel if you can associate one with your family. Good

luck!

About

the author: Margaret Ounsley has an MSc from the University of Oxford in

English Local History and is currently studying for a PhD in Poor Law History

at the University of Reading. She has written several local history books on Coley,

her local area in Reading, including Coley

Talking: Realities of life in old Reading, published last year.

A

technologically-challenged grandmother writes….

Some

time ago Peter published a newsletter article which suggested that for some

people, using DNA seemed like cheating, a way to get around doing good

old-fashioned research. Well, it certainly isn’t cheating, it’s simply a method

of confirming unproven ancestry, or opening up hitherto unavailable avenues for

further research.

Take,

for example, my family tree with the delightfully common surname of WILLIAMS in

Devon/Cornwall. Not as difficult as in Wales perhaps, but there are still

thousands of them. Even with access to all the appropriate local parish

records, it is still a nightmare trying to determine which John Williams or

William Williams is the correct ancestor, when several possibilities present

themselves in a given location.

Post-1837,

marriage entries list fathers’ names and occupations, which narrows down the

choice considerably, and successive census records can assist in tracking the

family through the decades. Wills listing descendants are another great help,

where they exist, as are the GRO birth indexes which give mothers’ maiden

names, but when all the obvious avenues have been investigated and 3 or 4

possible candidates still exist, where do you turn?

For

me there was only one answer, DNA – it’s a way of engaging the help of cousins

without necessarily contacting them. All it takes is for some of your DNA matches

to have a tree, and sometimes even a very small tree is sufficient.

As

an example, I had a DNA match which was shared with my sister, a 1st cousin and

two 2nd cousins on my maternal grandmother’s side. My genetic cousin had kindly

provided basic information of his parents, who married in Devon in 1938, but not

much else. Nevertheless, using a combination of GRO indexes and information found

at Ancestry, FamilySearch, and Findmypast I was able to draw up a reliable tree

back to my match’s great-great

grandparents. The maternal line offered no obvious links, but the paternal

line soon threw up the WILLIAMS surname in the area of Devon where my own

WILLIAMS ancestors lived.

Through

a process of elimination I arrived at my cousin’s 3G grandfather John Williams,

a man who was already on my radar as one of three possible candidates for my

own 3G grandfather (though up to this point I had believed one of the other John

Williams to be a more plausible choice). Finding a DNA match who was a

descendant of this different John Williams prompted me to research his other

descendants and, as I did, numerous surnames I recognised as DNA matches in the

4th-6th cousin range began popping up, providing further evidence to support

the case for this man to be my great-great-great grandfather.

All

in all, it was a very worthwhile, if time-consuming, exercise – but knocking

down a longstanding ‘brick wall’ is rarely easy. DNA had not only pointed me in

the direction of the correct John Williams, but also encouraged me to research

his descendants – I eventually found a dozen of his descendants who were DNA

matches.

There

is a certain thrill when tracing the tree of a DNA match, and a name which

already exists in your own tree appears. It not only confirms that your own

research is in all probability correct, but may provide the information needed to

extend your own tree back another generation. Approaching a ‘brick wall’ from a

different angle is a great way to knock it down!

I

am most definitely a DNA convert, though I admit to having no success

whatsoever with FTDNA, the first company I tested with. All my breakthroughs

have been via Ancestry, so I can understand why Peter recommends their test.

Many

thanks to Chris for taking the time to tell us about her experiences.

This

BBC News article

about three women of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force who won the Military Medal

for their bravery during the Battle of Britain was, fittingly, published just

hours before the lionesses of the England women’s soccer team defeated Germany

in a hard fought battle which – rather like WW2 – went to extra time.

The

daughter of one of those three brave women told the BBC how her mother was embarrassed

by the award, and rarely mentioned it – and some people thought that only men should

be awarded the Military Medal. Yet she had signed up for duty in December 1939,

long before most men volunteered (or were conscripted).

On

Thursday last week a new exhibition opened at Biggin Hill Memorial Museum - you can find out more here.

Gene

therapy that might have saved the Romanovs

Haemophilia

B, the disease inadvertently passed by Queen Victoria to the Royal Houses of Europe

has been cured by gene therapy, according to this BBC News article – which reports findings

published in the New England Journal of Medicine. This page

on the website of the National Hemophilia Organisation in the US has an

interview with British historian Helen Rappaport in which she explains the

impact that haemophilia had on the Russian Royal Family.

I

was particularly interested to read that the Tsesarevich was prescribed aspirin

by his doctors – though it may have temporarily quelled the pain it would have

made the bleeding worse (my mother made the same mistake in 1973 when I was

suffering from gastroenteritis). Rasputin may not have been a monk, and may or may

not have been mad, but his involvement did at least stop the doctors giving young

Alexei Nikolaevich a drug that would make his condition worse.

Note:

there’s another gene therapy on the horizon – scientists hope to be able to

cure an inherited heart condition that can lead to sudden death in young

people. You can read more here.

Somerton Man identified after 74 years?

I’ve

written in the past about the riddle of the man found dead in 1948 on an Adelaide

beach – and now the university professor who has been working on the case for

decades has come up with a name, based on DNA taken from the victim’s hair. You

can read all about the latest developments in this CNN article,

but I have a feeling that this story is far from over….

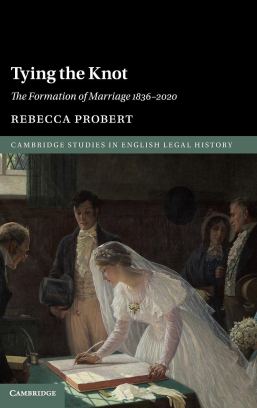

Tying the Knot: The

Formation of Marriage 1836-2020 is the latest book from Professor Rebecca Probert,

whose first book (see next review) has become a must-have for serious

genealogists with ancestors from England or Wales. It focuses on the

circumstances that led up to the passing of the Marriage Act 1836, the problems

that the legislation solved, and the problems that it created – some of which affect

us even today.

Tying the Knot: The

Formation of Marriage 1836-2020 is the latest book from Professor Rebecca Probert,

whose first book (see next review) has become a must-have for serious

genealogists with ancestors from England or Wales. It focuses on the

circumstances that led up to the passing of the Marriage Act 1836, the problems

that the legislation solved, and the problems that it created – some of which affect

us even today.

An

academic book in the Cambridge Studies in English Legal History series, it has

a price to match – and sadly this may prevent many readers of this newsletter

from purchasing it. However if you want to better understand why your ancestors

married how they did and where they did, I would encourage you to order the

book from your local public library, because it turns out that a lot of the

assumptions that family historians typically make about marriage in the 19th

century are false, or only applied for part of the period. For example, at one

point it was possible to have a religious ceremony in a register office!

Described

by Chris Barton, Emeritus Professor of Family Law at Staffordshire University

as “the stand-out family lawyer of her generation”, Professor Probert was an

advisor to the Law Commission, whose recommendations for changes to marriage

law I mentioned

in the last issue. She’s also no stranger to LostCousins members – indeed, it

was in this newsletter that she first invited family historians to submit

examples from their own researches, and amongst the long list of contributors

in the preface there are numerous names that I recognise.

This

book isn’t light reading – the copious footnotes are testament to that – but

there are so many surprises en route that there won’t be any chance of

nodding off (as I so often did when studying at university half a century ago).

Buy it if you can, borrow it if you can’t!

Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com Amazon.ca Amazon.com.au

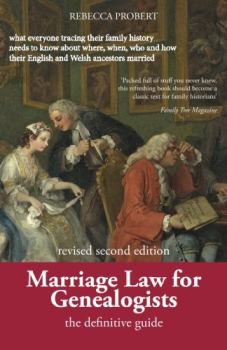

Review: Marriage

Law for Genealogists

When

I first reviewed Marriage Law for

Genealogists in 2012 I described it as "a phenomenal new book from

Professor Rebecca Probert of Warwick University, which proves that many of the

assumptions and assertions that have been made about marriage and related topics

such as illegitimacy are plain wrong!" (I went on to comment that even Ancestral

Trails, the book that taught me much of what I know about genealogy,

and which was written by a lawyer, isn't completely absolved of blame.)

Professor

Probert's book really was an eye-opener for me, as it must have been for

everyone who took my advice and bought it. For example, if you've ever wondered

about the status of clandestine marriages, then all will be revealed in the

book - it really is a goldmine of fascinating information! And whilst we all know

that divorce was rare until the 20th century, to discover that there were only

about 300 divorces up to 1857 (the first being in the 1660s) really puts it

into perspective.

Even

before reading the book I already knew that when my great-grandfather married

his sister-in-law in 1897 (after my great-grandmother died at the age of 36), he

was breaking the law – but it would be surprising if you don't have at least

one similar marriage in your tree. Indeed I found two more after reading the

book – so there are at least three in my tree, and that’s just on my mother’s

side! Key to  understanding how

marriage law worked in practice is the difference between ‘void’ and ‘voidable’

– and knowing which defects really mattered. For example, if only one witness

signed the register was the marriage void, voidable, or valid? After reading

the book you’ll know the answers – but would your ancestors have known

at the time?

understanding how

marriage law worked in practice is the difference between ‘void’ and ‘voidable’

– and knowing which defects really mattered. For example, if only one witness

signed the register was the marriage void, voidable, or valid? After reading

the book you’ll know the answers – but would your ancestors have known

at the time?

Despite

the title, Marriage Law for Genealogists

is not just about the letter of the law – Professor Probert carried out research

to establish how people behaved in practice. For example, if the bride and

groom gave the same address when they married did it mean they were co-habiting

prior to their marriage – or are there other possible explanations? Again, you

might be surprised by the answer.

This

is a book that every family historian who takes their research seriously should

keep on their bookshelves - so it's hardly any wonder that 10 years after its

original publication (a slightly revised edition was published in 2016) there

are no second-hand copies selling at bargain prices. Indeed, it's almost as

cheap to buy a new copy as a used one! This

is a book you’ll read and re-read.

At

£10, less than the price of a marriage certificate, it really is a must-have

purchase for anyone whose ancestors married in England or Wales – indeed, the only

book that comes anywhere near it is Professor Probert's follow-up, Divorced,

Bigamist, Bereaved which looks at how our ancestors' marriages ended.

As

usual, you can support LostCousins when you use the links below - even if you

end up buying something completely different.

Amazon.co.uk Amazon.com Amazon.ca Amazon.com.au

As

many of you will know, since the pandemic began I’ve foregone the pleasure of

shopping in favour of home deliveries (and the occasional click-and-collect, which

at our nearest Tesco supermarket takes place outdoors). But I still take

pleasure in checking the bills – it must be the accountant in me!

A

few months ago Tesco discontinued paper delivery notes in favour of emailed

receipts which, in theory, show each item in the order and the price paid

(though just to confuse things some savings are deducted above the line and

some below the line). However, when I order two of an item which is sold by weight

(for example, my most recent order included two packs of kippers priced at £1.12

and £1.38) only one of them shows on the receipt, though both are included in

the total at the bottom of the bill.

When

I pointed this out to a very helpful gentleman in Customer Services I was

surprised to learn that it hadn’t been reported by anyone else – I can only

guess that other customers are more likely to be bean eaters than bean

counters. Or perhaps they’re just more trusting than I am….

I

don’t mind occasionally going to collect my order, but I didn’t appreciate what

happened 5 weeks ago when a delivery I was expecting failed to show up. Having

waited for more than half an hour beyond the arranged delivery slot I phoned Customer

Services, who were at first as stumped as I was. Eventually they managed to get

through to someone at the store (which by this time was closed), only to

discover that I should have been notified that, due to a driver shortage, my

delivery had been switched to click-and-collect. Thankfully there was a member

of staff who could hand over the order, even though it was outside normal

hours, and on returning home I was mollified by the arrival of two separate emails

with £10 goodwill voucher codes.

All’s

Well That Ends Well – to quote Shakespeare – except that it turned into The Comedy

of Errors, because when I subsequently tried to use the ‘goodwill’ vouchers towards

future orders they weren’t accepted. It transpired that this problem was

something that my saviour in customer services was aware of, and he told me

that the technical team were working on it – though he suggested that I might

prefer to have a refund, as he didn’t know how long it would take, and wasn’t

sure that that the vouchers I had been issued with would ever work. I gratefully

accepted this suggestion!

But

these are all First World problems – and the almost total loss of our water

supply yesterday, resulting from a burst water main, made me realise how fortunate

we are to have fresh water on tap, something that most of our ancestors could

only have dreamt of.

Coincidentally

we had a plumber in yesterday afternoon to change some taps, service our boiler,

and carry out a few other repairs that had been patiently awaiting his arrival –

the lack of water did at least mean that he didn’t have to keep switching it

off at the mains! I gave him one of our masks to wear since he only had one of

those blue things that they hand out to people who turn up at the doctor’s

surgery without a face covering – I explained that several of our friends and

relatives had caught COVID for the first time during July, and we were

determined not to join them. It’s not so much the risk of dying from the

disease, which is lower with the Omicron variants, but the chance of developing

long COVID (which can affect anyone, even youngsters). I experienced something

similar after catching dengue fever in 2013: it was followed by two years of feeling

tired, and there are some (thankfully minor) symptoms that have never gone away

– so you can understand why I wouldn’t want to go through the same thing again.

The

masks my wife and I wear are available from Amazon in the UK (follow this link to see the full range); you can also

buy them direct from the manufacturer. Lateral flow kits are another key part

of the jigsaw, and we’ve managed to find a reasonably-priced source of the same

kits that we used to get free from the NHS, so we can be confident that they’ve

got all the right approvals – you’ll find them here.

Infections

are at last starting to fall in Britain, though with 1 in 20 of the population

infected it’s not a good time to cast caution to the winds. On the other hand,

winds are just what we need to disperse virus particles in the air – which is

why it is so much safer meeting people outdoors!

This is where any major updates and corrections will be

highlighted - if you think you've spotted an error first reload the newsletter

(press Ctrl-F5) then

check again before writing to me, in case someone else has beaten you to

it......

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2022 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of

the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the website are affiliate links –

if you make a purchase after clicking a link you may be supporting LostCousins

(though this depends on your choice of browser, the settings in your browser,

and any browser extensions that are installed). Thanks for your support!