Newsletter – 30th

April 2023

19th Birthday

Issue

Claim your relatives

before someone else does!

Hampshire marriages

1754-1921 now online

MASTERCLASS: Tracking

down pre-1837 baptisms and marriages

Knocking down a ‘brick wall’ using the GRO indexes

Big savings on Who Do You Think You Are? subscriptions EXCLUSIVE OFFER

Findmypast end

partnership with Living DNA

Which DNA test should

you buy?

Save on Ancestry DNA US ONLY

The LostCousins

newsletter is usually published 2 or 3 times a month. To access the previous issue

(dated 24th April) click here; to find earlier articles use the customised Google search between

this paragraph and the next (it searches ALL of the newsletters since February 2009,

so you don't need to keep copies):

To go to the main

LostCousins website click the logo at the top of this newsletter. If you're not

already a member, do join - it's FREE, and you'll get an email to alert you

whenever there's a new edition of this newsletter available!

I’m

not very good at waiting, especially when I don’t know what’s going on, or how

long I’m going to have to wait. More than half a century ago I walked out of a

theatre because I was tired of Waiting for Godot. Later I found out that

he never does show up, so it was probably a good decision: apparently one literary

critic described the play as “nothing happens – twice”.

50

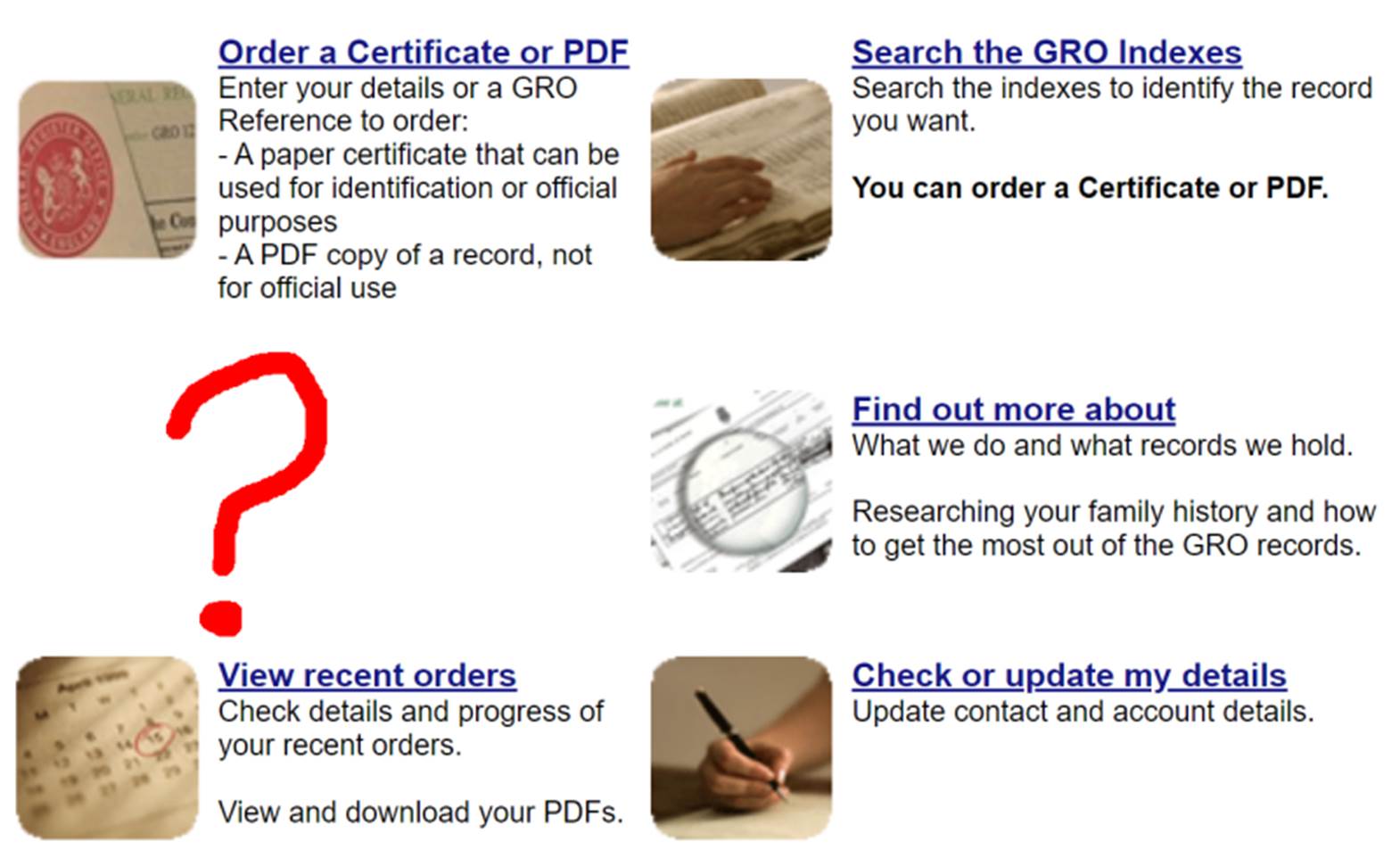

years on there’s another mystery that may have been puzzling some of you – why is

there a big hole in the main menu at the General Register Office (GRO) website?

No

doubt at some point the GRO are going to make an announcement of great interest

to those of us who have ancestors from England & Wales. But I can’t tell you

what they will be announcing or when it’s going to happen.

Let’s

hope that they don’t make family historians wait too long….

Claim your relatives before someone else

does!

Looking at the LostCousins database statistics I can

see that 91.9% of the people recorded on the 1881 England & Wales census

have yet to be claimed by anyone. For the Scotland 1881 census it’s 96%, and

for the Canada 1881 census it’s an amazing 98.4%!

When

I set up LostCousins 19 years ago I had two primary objectives – one was to connect

family historians researching the same ancestors, so that they could

collaborate. The other, which I call ‘Project 1881’ was to link the people

recorded on the 1881 Census with living relatives, so that all researchers –

including social historians and local historians – could carry out studies that

would otherwise be practically impossible.

As

we all know, tracing back from 2023 to 1881 is fairly easy,

but tracing forwards from 1881 to 2023 can be extremely difficult. Mapping an

entire population over centuries isn’t a new idea: this article

about Iceland will give you some idea of what England, Wales, Scotland, and

Canada might be able to achieve – with your help.

Please

take a moment to identify your relatives on the 1881 censuses, and add them to

your My Ancestors page. If it turns out that another member has already

entered the same relative you can exchange information and collaborate, but if you’re

the first to claim that person you’ll be establishing an important link from

the past to the present.

At

a time when there are so many terrible things going on in the world, let’s show

that we can work together for the common good!

Over

the past 6 months there’s been a lot of discussion in the media about artificial

intelligence, so you might be wondering when we can expect an AI to research

our family history so that we don’t have to do it ourselves.

If

that day ever arrived it would take all the fun out of it, for me at least – I’d

have to find something else that could provide the same challenges and the same

rewards. And, I suspect, the same disappointments and

the same frustrations!

General

purpose AI models are trained by scraping, analysing, and processing publicly-available

data from the Internet – something that is giving rise to concerns about privacy

and plagiarism. But when it comes to family history, my concern would be that online

trees would inevitably be one of the main sources of data, and we all know how

unreliable many of them are!

However,

I do think we will see companies like Ancestry not only upgrading their hint-generation

algorithms, but also providing tools to enable users to carry out checks on their

own trees. Perhaps eventually this will improve the quality of online trees to

such an extent that further automation will be possible?

Hampshire marriages 1754-1921 now online

It

looks as if Ancestry are going full steam ahead with Hampshire parish registers

(see the last issue for a guide to which parishes will and won’t be included).

Marriage registers from 1754, when pre-printed volumes were introduced, to 1921

are now online and indexed – the link below will take you to the search page:

Hampshire,

England, Church of England Marriages and Banns,

1754-1921

In

the next article you’ll find a list of all the parish registers that you’ll

find online at either Ancestry or Findmypast….

MASTERCLASS: Tracking down pre-1837 baptisms

and marriages

Researching ancestors who lived in England & Wales is usually fairly straightforward until we get back to 1841, the date of

the first census, and 1837, the year that civil registration began. But then it

becomes much tougher, for a number of inter-related

reasons. In this Masterclass I'm going to first talk through the problems,

and then explain how you can overcome them.

Why we need to use different techniques

When we're researching after 1837 we can

refer to the GRO indexes, which (in theory at least) list everyone who was

born, or married, or died in England & Wales. Once we get to 1841 we can also refer to censuses which (again, in theory)

list everyone in the country on a certain night. Best of all, those indexes and

censuses are available online, so anybody anywhere can get access to them.

But before 1837 we don't have either of those available to us -

prior to the introduction of civil registration parish registers are by far the

best sources of early information (and often the only surviving documents that

name our ancestors). Most people were baptised, most of those

who have descendants alive today got married, and the one thing you can be sure

of is that they eventually died, in which case they'll almost certainly have

been buried somewhere.

However, even though the vast majority of

parish registers have survived, at least from the 17th century onwards, they're

scattered across the nation rather than held in a central store. In most cases

the original registers are held by the county record office, which means you

cannot go to any one record office – not even the National Archives – and

expect to find all the baptisms for (say) 1797. Indeed, even if you visit the

repository of the registers you're seeking the chances

are you'll only be able to view them on microfilm – and microfilmed entries can

be hard to decipher.

Many registers have been transcribed, often by volunteers, and in

some cases the transcriptions have been made available online. However you can't just go to one website and search through

every parish register that has ever been transcribed, because some

transcriptions are available at one site, some at another - and even if you

have the time to visit them all, many of the transcriptions are only available

at subscription sites, so you may not be able to access them. Furthermore, some

of the transcriptions are only available on CD ROM or on microfiche - usually

through family history societies - and there still many registers have NEVER

been transcribed.

Faced with such a different situation some faint-hearted researchers

just give up – research pre-1837 is so different that they are scared to even

try. Some try, but fail – either because they don't

fully understand how best to make use of the available resources, or because

they don't realise just how much is available to them. And then there are those

who pick an entry simply because it's the only one they can find – or because

the website they use has 'hinted' that it’s the entry they're looking for.

Tip: in the world of genealogy ‘hints’ are not clues to the

correct answer, simply suggestions for research.

Because of the way that records are scattered across the country,

across the Internet, and across different media, it's tempting to adopt an unfocused

"where shall I try next" approach. Now, I'm not a professional

genealogist, but one thing I do know is that professional genealogists always

search logically and methodically, and above all they record where they

have searched and what they have searched for. In the days

when I was still able to provide one-to-one research help to every member I'd frequently

be told "I've searched everywhere" yet when pressed they couldn't

tell me which parishes they'd searched, which periods the searches covered, or

even - in some cases - precisely what surnames and spellings they looked for.

Start by gathering evidence

First collect all the evidence that indicates - no matter how

obliquely - where and when your ancestor is likely to have been born. Sources

of information will often include early censuses, marriage certificates, and

death certificates – all of which can be helpful, but

can also be misleading.

The fact is, many people didn't know where they were born, so

often the birthplace they gave when the enumerator came round is the place – or

one of the places – where they grew up. Similarly, some people didn't know how

old they were – they might have known when they were born, but

that isn't the question on the census form. It asks for their age, and not

everyone was capable of subtracting one year from another, particularly if the

years were in different centuries.

Remember too, that it was the householder who was responsible for

completing the form (or supplying the information to the enumerator) - the ages

and birthplaces of adopted children, stepchildren, servants and visitors are

particularly likely to be incorrect. Ages can also be ‘massaged’, perhaps to

reduce a large gap in age between husband and wife, or to reduce the age of an

unmarried daughter. And after a certain age people are more likely to add years

to their age, rather than subtract them.

Don’t be fooled by the evidence

Regard the information you have as ‘hints’ rather than as ‘facts’ –

our ancestors may not have intended to mislead us, but all too frequently the

records they left behind can lead us up a blind alley.

If your ancestor married after 1837 you may have a clue to the

name and occupation of their father – but bear in mind that this can be misleading,

and sometimes it is completely wrong. This is particularly likely if the person

concerned never knew their father – either because he wasn’t married to their mother,

or because he died at an early age.

Something else to watch out for is the possibility that your

ancestor was born before their parents married, as in the case of my

great-great-great-great-great grandmother Elizabeth Wakefield, who was baptised

3 weeks before her parents married, and appears in the register as “Elizabeth

the daughter of Ann Eels a bastard”. Fortunately the

marriage is on the same page of the register so I could hardly miss the baptism,

but if I’d been relying on transcribed records it could have been very different.

Elizabeth was the eldest of 8 children, but there’s another reason

why the baptism of the eldest child can be hard to find. Some women went home

to their own mother to give birth to their first child, and even if that wasn’t

the case, they may have chosen to go back to their home parish and the church

where they married for the baptism.

Look out too for late baptisms – some children were baptised as

teenagers, or even as adults. I’ve come across parents who were baptised on the

same day as their own children!

Find out what's available online

When I began researching my family tree there was very little

information available online – only one England & Wales census and not a

single parish register. Most research had to be carried out at local record

offices, or at the Family Records Centre in London, which opened in 1997 and

closed just over a decade later. (Those who started before I did have memories

of visiting St Catherine's House, Alexandra House, or Somerset House; some

recall making appointments to inspect parish registers when they were still

held at the church.)

These days there is a wealth of records online, including parish

registers from many areas. But whilst most of the registers that are online (and

many that aren't) have been indexed there is no single source you can go to,

and many of the registers and indexed transcriptions are behind paywalls. It's

therefore very tempting to search a handful of sites and ignore the others.

Beginners especially are often tempted to take the first entry that

fits and add it to their tree, even if the name is such a common one that a more

comprehensive search would throw up dozens of alternatives. The most blatant errors

are usually made by those whose knowledge of geography is limited by their inability

to look at a map!

FamilySearch

A good place to start your search is the FamilySearch website – it's

free, but you will need to register. At one time the International Genealogical

Index (IGI) at FamilySearch was the key source for family historians, with more

parish register entries than all other websites added together. However, over

time the IGI gained a poor reputation because of the way that transcribed

entries from registers were interspersed with entries from Bishop's Transcripts,

and – more dangerously – entries submitted by individuals that usually had no

documented source, and in some cases seemed to be no more than conjecture.

When the FamilySearch site was relaunched more than a decade ago

the IGI temporarily disappeared. When it returned it had been completely

transformed – the entries had been split between Community Indexed (those

added as part of an organised transcription project), and Community

Contributed (added by individuals). Subsequently the indexed entries were split

into individual record collections, but you can still search them by following

this link.

If you don't find the entry you're

seeking in the IGI it's usually because the register that contains the entry

hasn't been transcribed and included in the index. Although FamilySearch has at

some point microfilmed most of the surviving parish registers, only about half

have been transcribed and indexed – so half the baptisms and marriages you're

looking for won't be in the database at all. Furthermore, hardly any burials

for England & Wales are included in the IGI.

How can you find out which entries are included?

The simplest way is to refer to Steve Archer's site (which

covers Scotland and Ireland as well as England & Wales). As well as listing

the years of coverage by parish and by event the site also gives the relevant batch

numbers - searching by batch number is not only a great way to limit your

search to a specific parish, it's a great way to overcome transcription errors or

entries that have been recorded incorrectly by the clergyman who conducted the

service (when you omit the person's name you'll get a listing of all the

entries in the batch).

What should you do if the parish you're interested in is included

in the IGI, but you still can't find the entry you're looking for despite

searching through the relevant batch (in case there has been a major

transcription error)? This suggests that the event didn't take place where you

think it did, or when you think it did – or it didn't take place at all (not

all children were baptised, and not all baptisms were recorded in the register,

especially between 1783-94 when Stamp Duty was charged).

Find out which other parishes are nearby

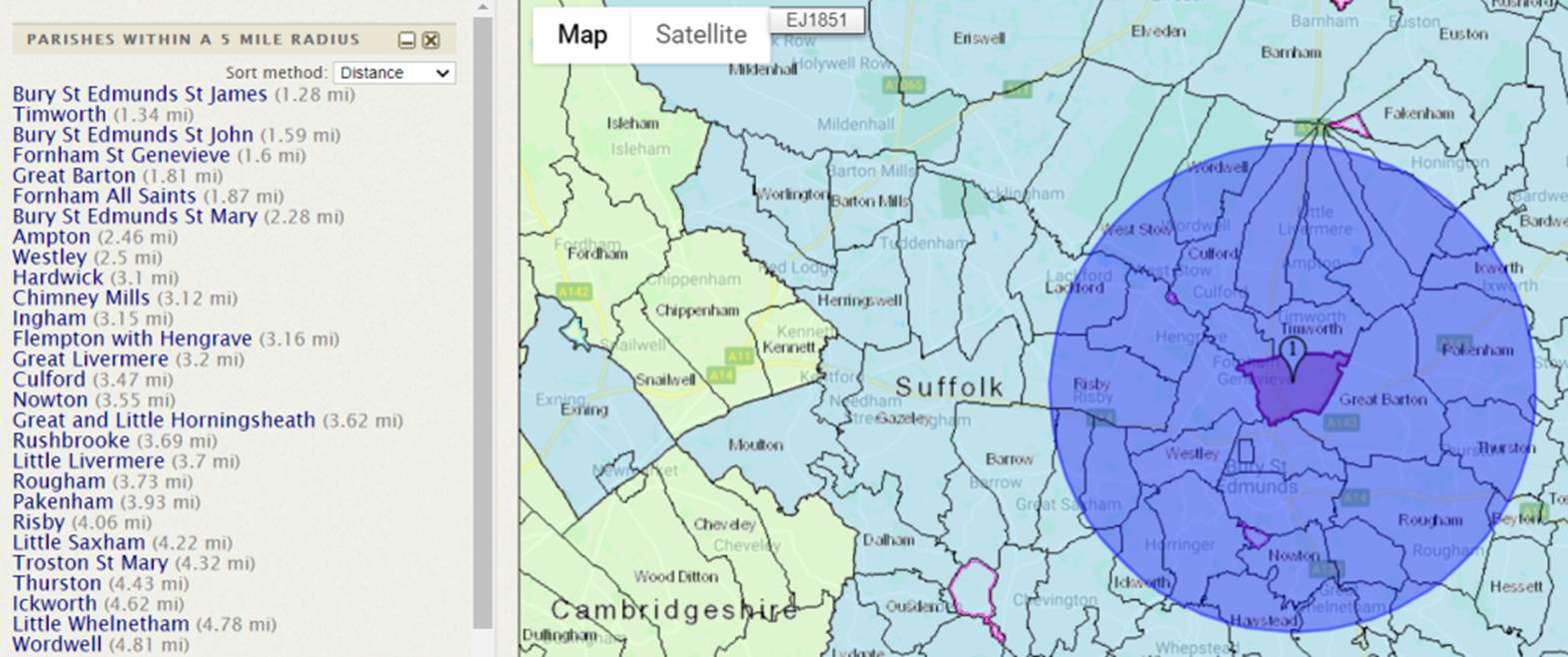

There are at least two ways to do this. One is to use a 'parish

locator' (such as the free ParLoc program)

to get a list of all the parishes around the town or village where you believe

your ancestor to have been born or married. In the country you might use a 5 mile radius, but in London that could give you a list of

100 or more parishes - so a radius of 1 or 2 miles might be more appropriate.

Tip: the nearest parish church may have been in a different parish

- the size and shape of parishes varies enormously, and some parishes were

split into two (perhaps because two older parishes had been combined).

Another option is to use the maps at FamilySearch -

start with the parish where you had expected to find the baptism or marriage,

then use the Radius Search (found on the Options tab). For example,

when I was looking for the baptism of my great-great-great-great-great grandfather,

who married at Fornham St Martin in Suffolk in 1763 I

got these results:

It was quite sobering to discover that there were 28 parishes

within a 5 mile radius of Fornham

St Martin. I eventually found the baptism I was looking for in a parish that

was 9 miles away – there were 84 other parishes which were closer, a daunting

number if the only resources available were a microfiche reader and a drawerful

of microfiches.

If you haven't been able to find the baptism or marriage you're

looking for in the IGI this strongly suggests that it's recorded in a register

that isn't included in that index, so you should go back to Steve Archer's

invaluable website to find out which parishes aren't included in the IGI for

the relevant period - and they’re the ones that to focus your attention on.

Tip: many FamilySearch records will also be found at Ancestry

and/or Findmypast; similarly Findmypast have provided FamilySearch with indexed

census transcriptions. Being able to search the same records at multiple

websites can be useful, but be careful not to pay for records that you could

get for nothing elsewhere!

Although you can search all of the

transcribed parish register entries with a single search from the FamilySearch

home page, you won't find any records that are only present as unindexed

images. It's therefore essential that you're aware of the unindexed images

at the FamilySearch site that may be of relevance to your research.

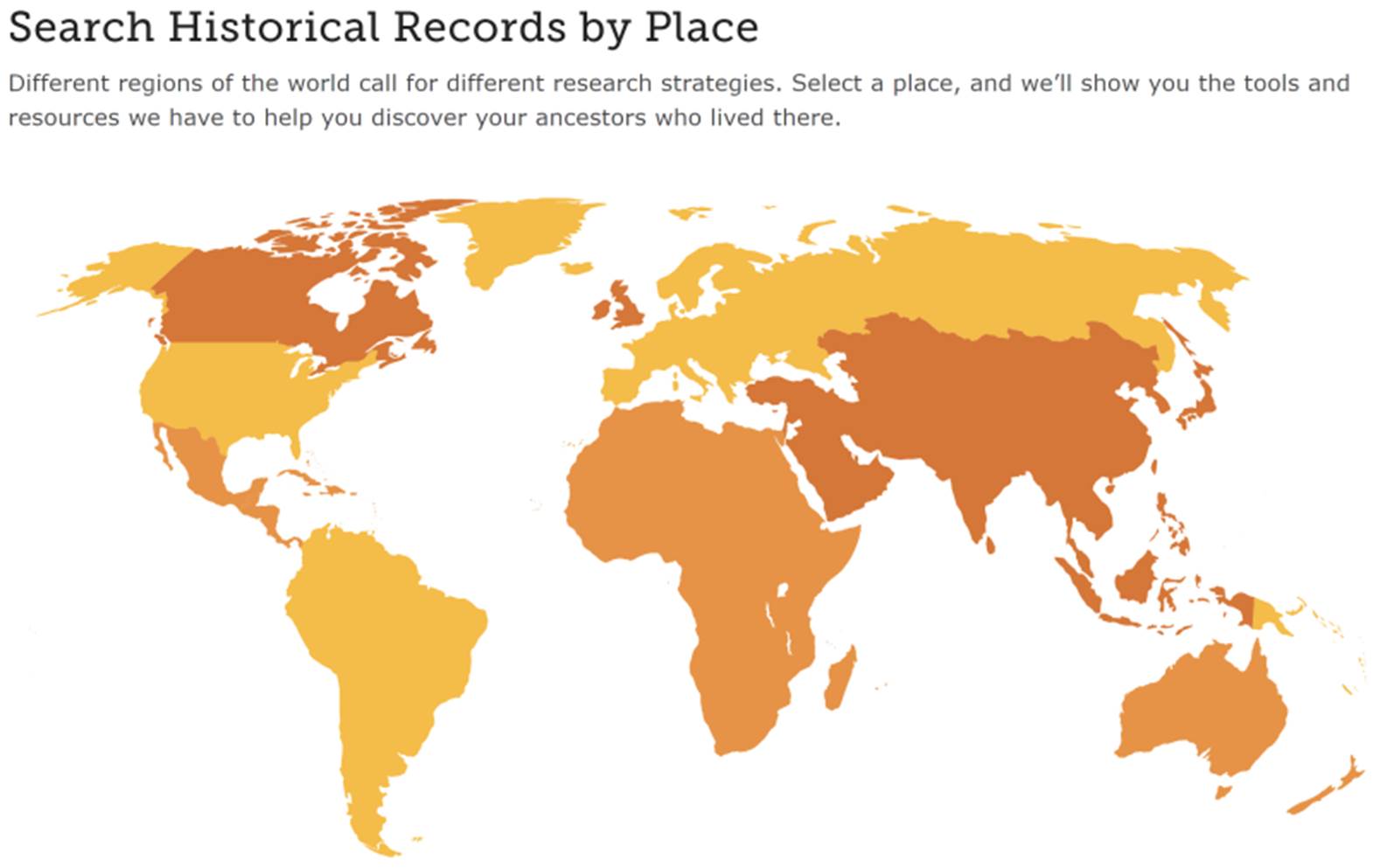

To find out which records FamilySearch has for a particular

country, click on the map that you'll find here.

The list of records is divided into two sections, Indexed

Historical Records (which may or many not include images) and Image-Only Historical Records.

A camera icon indicates which of the transcribed record sets have images

associated with them, but this doesn't necessarily mean you'll be able to view

those images, as some are only available within an LDS Family History Centre or

affiliated library (such as the Society of Genealogists Library).

As regular readers of the LostCousins newsletter will know,

sometimes there can be images which are available to all users of the

FamilySearch site, but are hard to find. The best way

to find out what records are available for a particular parish is to carry out

a Catalogue search.

Tip: an often overlooked feature of the new FamilySearch site is

the 'wiki', which provides information about individual parishes, often

including details of online sources of register transcriptions and/or images at

other sites (follow this link to see an example). I find that the

easiest way to find a parish within the wiki is to use a Google search, for

example 'familysearch wiki great barton'.

Another free site with a large collection of transcriptions

is FreeREG – at the time of writing it had over 28 million baptisms, nearly

9 million marriages, and over 20 million burials in its database. However,

they're not evenly spread across the country: some counties are very well

catered for, but others less so – however it's fairly easy

to see what is and isn't there. Other volunteer-led projects include the Online

Parish Clerk sites: they don't exist for every county, but the counties with by

far the best coverage are Cornwall,

with over 4 million parish register entries, and Lancashire with

over 10 million records.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the contents of some

parish registers were published as books, and your best chance of finding them

is through sites such as the Internet Archive, another free site, where a search

for (say) 'Kent parish registers' brings up a long list of registers that have

been printed in book form and digitised for all to see (you might pay to see

some of these records at subscription sites). Another similar site is Google Books.

Inevitably there is a big overlap between the two.

A straightforward Google search is always worth trying, as quite a

few individuals have transcribed parish registers and posted the results on

their own websites. Some record offices have information that you can search

free online: for example Hertfordshire has a range of records

including a marriage index, whilst Medway Archives have posted registers for

their part of Kent online (not transcribed, but at least they are at your fingertips

– and free).

Subscription and pay-per-view sites

An increasing number of parish registers and/or register entries have

become available online at Ancestry and/or Findmypast, with further counties

due to come online in 2024.

When I first wrote on this topic in February 2010 there were NO

register images available at either site, but now you can search Bexley,

Birmingham, Bristol,

Derbyshire,

Devon, Dorset,

Gloucestershire,

Hampshire,

Lancashire,

Liverpool,

London,

Manchester,

Norfolk, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire,

Oxfordshire,

Somerset,

Surrey,

Sutton,

East

Sussex, West

Sussex, Warwickshire,

Westminster,

Wigan, Wiltshire,

Worcestershire,

York,

North Yorkshire,

West

Yorkshire, and most of Wales

at Ancestry, and Cheshire,

Devon, Hertfordshire,

most of East Kent,

Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Plymouth

& West Devon, Portsmouth,

Rutland, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Surrey,

Warwickshire, much of Yorkshire,

and most of Wales

at Findmypast. Ancestry also have parish registers for Jersey,

and a selection from Cornwall,

whilst Findmypast who used to have Westminster

register images, still have a complete transcription of the registers.

Ancestry also have indexed transcriptions of Essex

registers, with links to the register pages at the Essex Archive Online site (see

below – this requires a separate subscription). Ancestry are

also in the process of digitizing Suffolk registers, and have finished

scanning Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire registers – they should

be online during 2024.

Note that there is relatively little duplication – archives

generally license their records on an exclusive basis, at least for the first 5

or 10 years, which is why most serious researchers end up subscribing to both of the two big sites (though not necessarily at the

same time). Many public libraries, especially in England, have a subscription

to Ancestry or Findmypast, sometimes both - so it's worth checking what's

available in your area.

Tip: many cities and metropolitan boroughs have a record office

which holds the registers for their area, so that, for example, the Lancashire

collection at Ancestry doesn't include records for every town that was

originally part of the county. However Findmypast's

Cheshire collection does include Stockport, and also Warrington - which is now

in Cheshire, but was previously part of Lancashire.

Although there are no images, the National

Burial Index at Findmypast has over 16 million entries from England &

Wales, and most of the entries are pre-1837. Findmypast also has an extensive

range of transcribed parish records thanks to their relationships with the

Society of Genealogists and the Federation of Family History Societies.

Durham Records Online has over 4 million

transcribed records from County Durham and Northumberland. The Joiner

Marriage Index has over 3 million marriage records from more

than 5000 parishes in 39 counties.

Essex

Record Office offer online access to most of their parish

register collection through Essex Ancestors - and whilst the subscription is

quite steep at £95 a year (the cheapest subscription is £20 for one day), the

quality of the images is excellent; many Essex wills are also included. Essex

Ancestors do not provide an index to their register entries, but Ancestry have indexed

the Essex registers (and link to the images on a pay-per-view basis). If you

have an Essex Ancestors subscription this article

explains how to use it alongside the Ancestry transcription – the tips will

save you lot of time.

Society of Genealogists library

Many of the largest collections of transcribed records held by the

Society of Genealogists are available online to members: these include Boyd's

Marriage Index, which has particularly good coverage in some of the counties (eg Suffolk and Essex) that

are least well represented in the IGI; for a list of all

the online collections click here.

Many of the records, including Boyd's Marriage Index are also available

through Findmypast.

The Society of Genealogists has many more records in its library,

including an amazing collection of records on CD ROMs and microfiche collected

by family history societies and other organisations. In August 2017 an enormous

collection of microfilms which were previously held by the LDS London Family

History Centre was added. Non-members can use the SoG

library on payment of a fee of £10 for half day or £20 for a full day - more

details are available here.

Family history societies

Many family history societies have transcribed parish registers

and headstone inscriptions, and often these are made available as CD ROMs or

digital downloads; some have online indexes (usually only available to members),

others offer a lookup service (chargeable).

Tip: although some family history societies have made records

available through Findmypast, their own record collection is likely to be more

extensive and more detailed.

Record offices and archives

When you're within striking distance of the relevant record office

there's no substitute for visiting in person - but check first what's available

online so that you don't waste your time there looking up records you could

just as easily (or perhaps, more easily) have searched from the comfort of your

own home. When I was beginning my research I wasted a

lot of time searching parish registers that had already been indexed for the

IGI - I should, of course, have focused on the unindexed parishes.

Many record offices and archives will do research on a paid basis

- charges range from £30-60 per hour, which sounds a lot but in my experience

is usually money well spent. However independent researchers may charge less, and

some record offices will provide a list (especially if they don't offer a research

service themselves). Please bear in mind that the

inclusion of a researcher on the list is not necessarily an endorsement of that

researcher, but local knowledge can be invaluable.

The importance of the Register of Banns

One of the key reasons we search for the marriages of our

ancestors is to find out the maiden names of our female ancestors (of course,

if they gave birth after 1837 you'll usually find this

information on the birth certificate). If the couple lived in different

parishes, which was not unusual, they had to decide which one to marry in – and

typically it would be the bride's parish that was chosen. This creates a slight

problem, because unless she survived until the 1851 Census we won't know where

she was born (and even then, it wouldn't necessarily be the parish where she

was living at the time of her marriage).

Fortunately the

banns register often comes to our rescue. Most people married by banns, rather

than by licence, and if the couple lived in different parishes the banns would

necessarily be read out in both, and so would be recorded in the Banns register

for both parishes. However, there are not nearly as many banns

registers available online as marriage registers – you're more likely to have

to have to pay a visit to the record office.

Marriage licences, bonds, and allegations

There is an excellent guide in the FamilySearch wiki – you’ll find

it here.

Don’t assume that just because your ancestors were poor they married by banns:

for example, if they came from parishes that were a long way apart it could

have been expensive to arrange for banns to be read in both parishes.

Non-Conformists, Catholics, and Quakers

Between 1754 and June 1837 Non-Conformists and Catholics couldn't

legally marry in their own churches, so discovering that your ancestors married

in their local parish church doesn’t mean that they belonged to the Church of

England. Nor does finding out that your ancestors were buried in the parish

churchyard – not all chapels and meeting houses had their own burial ground.

The religious census of 1851 found that as many people attended Catholic or

Non-Conformist churches as attended the Church of England, although attendance and

allegiance are not the same thing.

By far the best source of Catholic registers is Findmypast – you can

see what they have to offer here.

Many Non-Conformist registers were sent to the General Register Office in the

19th century and ended up in the National Archives – key sources include Ancestry,

The Genealogist,

and Findmypast.

Using the

GRO's new online birth indexes

In November 2016 the General Register Office made available online

indexes of births and deaths which include additional information. In particular,

the mother's maiden name is now shown in respect of births from 1837 onwards,

which not only makes it easier to locate the right birth entries, it might

enable you to knock down a 'brick wall' without purchasing the relevant

certificate(s), or finding the marriage. Also consider that whilst your

ancestor might have been born before 1837, she might have a younger sibling who

was born afterwards.

And finally…..

Remember that people didn’t stop baptising their children when

civil registration commenced in July 1837, and most married in church even after

they had the option of marrying in a register office.

Note: although this Masterclass relates to records from England

& Wales, many of the techniques described can also be applied to research

in Scotland, Ireland, and some other countries.

Knocking down a ‘brick wall’ using the GRO indexes

Earlier

this month I published an updated version of the Masterclass Finding birth

certificates. Reading it reminded Jane that at Findmypast it’s possible to

search by maiden name, even for births before 1911 (when the maiden name was

first added to the quarterly indexes).

More

importantly, it’s possible to search by the mother’s maiden name without specifying

the father’s surname – something that the search at the GRO site doesn’t allow –

and this is how Jane managed to make a breakthrough:

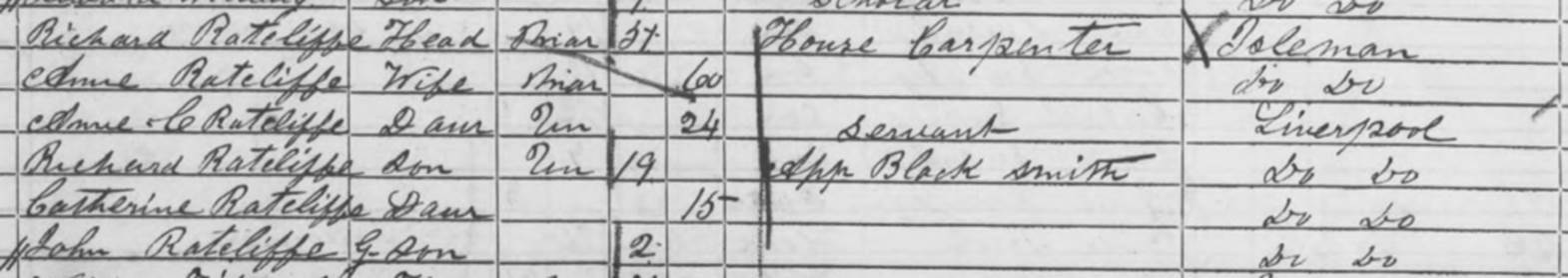

I have been a subscriber for some years and

have always read your newsletters with great interest. Many times

I have been helped by your tips, but never more so than after reading your March

29th newsletter!

Using the information about mothers’ maiden

names being given in the GRO indexes I had another go at finding the birth of

my great grandfather John James Radcliffe around 1858/9 - it had eluded me for

20 years! The first mention I hasd been able to find of

him was as John Ratcliffe in the 1861 census, living in Boundary Street,

Liverpool with his grandparents and possible mother Anne.

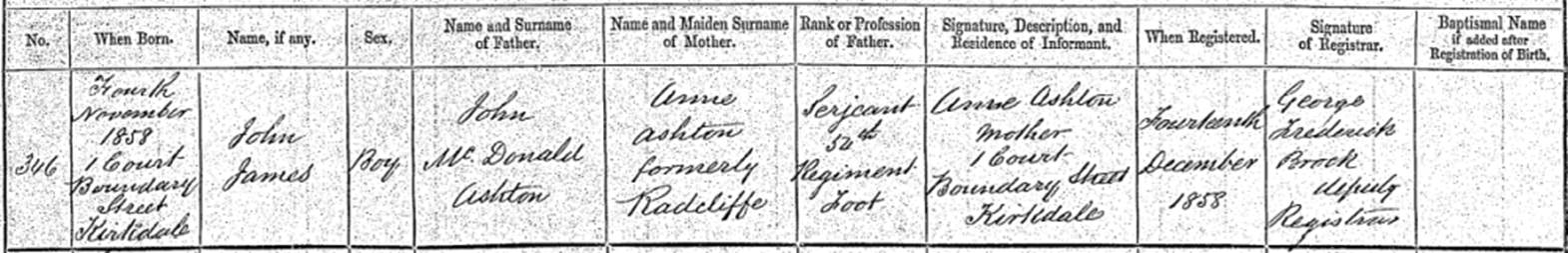

© The National Archives – All Rights

Reserved. Used by kind permission of Findmypast

When I searched the birth indexes at

Findmypast without a surname, but using Radcliffe as his mother’s maiden name I

found this entry:

The PDF copy of the birth register entry

showed that he was born in Boundary Street, Liverpool to Anne Ashton formerly

Radcliffe and John Mc Donald Ashton, a soldier:

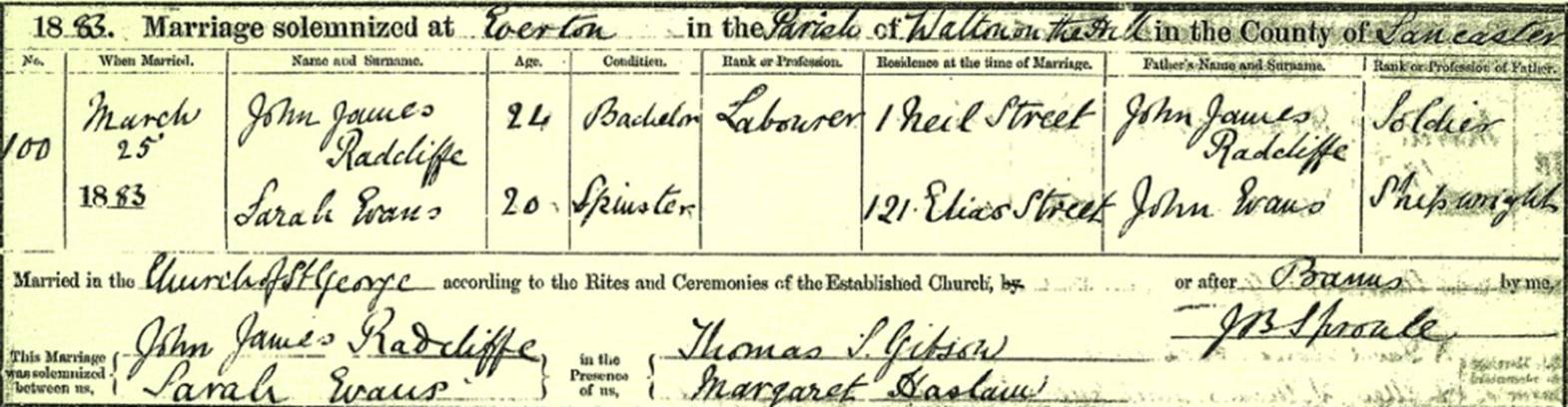

This fitted perfectly, because when John

James married in 1885 he said that his father was a soldier:

In addition my

cousins and I have Scottish ancestry in our DNA and we guess it may come from

John McDonald Ashton – so all of this seems to fit. I subsequently found his baptism

in March 1859 at St Peter’s church where all the Radcliffes

had been baptised, but once again his surname was shown as Ashton.

Well

done, Jane – it just goes to show that the best way to knock a longstanding ‘brick

wall’ is to do something you haven’t tried before!

Big

savings on Who Do You Think You Are? subscriptions EXCLUSIVE

OFFER

The

exclusive offer I’ve arranged for LostCousins members is still running but

please note that it applies only to print copies, not the digital edition.

I've

been a reader of Who Do You Think You Are? magazine ever since issue 1,

and I can tell you from personal experience that every issue is packed with advice

on how to research your family tree, including how to track down online records,

how to get more from DNA tests, and the ever-popular readers' stories. Naturally

you also get to look behind-the-scenes of the popular Who Do You Think You

Are? TV series.

There's

an extra special introductory offer for members in the UK, but there are also offers

for overseas readers, each of which offers a substantial saving on the cover

price:

UK - try 6 issues for just

£9.99 - saving 68%

Europe - 13 issues (1 year)

for €65 - saving 33%

Australia

& New Zealand

- 13 issues (1 year) for AU $99 - saving 38%

US

& Canada

– 13 issues for US $69.99 – saving 59%

Rest

of the world

- 13 issues (1 year) for US $69.99 – saving 41%

To

take advantage of any of these deals (and to support LostCousins) please follow

this link.

Findmypast end partnership with Living DNA

Since

2018 Findmypast have been selling tests on behalf of Living DNA, a British

company – but it was announced this week that the arrangement has come to an

end. If you want you

can still buy a test direct from Living DNA, but there are better options for family

historians – see the next article.

Which DNA test should you buy?

There

are lots of companies offering autosomal DNA tests, some of them well-known

names in the world of genealogy, and some you’ve probably never heard of

before.

DNA

expert Debbie Kennett recently reviewed the most popular tests for Who Do

You Think You Are? magazine, and only one of them got a 5* rating – the

Ancestry DNA test, which is also the only autosomal DNA test that I’ve recommended

in recent years.

Ancestry

has by far the biggest database of DNA results, which not only means that you’ll

make more matches that can help you knock down your ‘brick walls’, it also

enables Ancestry to do things that most other providers can’t.

For

example, SideView enables Ancestry to predict – with a

high degree of accuracy – which of your matches are on your maternal side, and

which on your paternal side. This might seem like a small thing, but it means

you’ll be less likely to waste time looking for connections that don’t exist. For

example, if a genetic cousins has one of your ancestral surnames in their tree you

might assume that this where the connection will be found – but if the SideView prediction is that you’re connected on the opposite

side of your tree, youll probably want to think

again.

However

the two best things about testing with Ancestry is that you don’t need to know

anything about the technical side of DNA are:

- You don’t need to know anything

about the technical side of DNA

- ThruLinesTM and Common

Ancestors make use of Ancestry’s enormous collection of family trees

to make sense of the connections between you and your genetic cousins

To

knock down longstanding ‘brick walls’ usually requires you to utilise conventional

records-based research as well as clues from DNA, so the way that Ancestry

integrates family trees with DNA is a big plus point for users like you and me.

In

her 5* review Debbie highlights just two things that you might consider a

disadvantage: one is that you cannot transfer DNA results from other test providers

– though actually that’s a good reason for choosing Ancestry, especially since

you can transfer your Ancestry results to other sites to find more DNA matches

(if the 10,000 plus you get at Ancestry aren’t enough!).

The

other thing to consider is that without an Ancestry subscription you can only

see four generations of your matches’ ancestors – unless they invite you to view

their tree (which they probably will if you ask, especially if it is a public tree).

On the other hand, many serious family historians already subscribe to Ancestry

– and only one person in the extended family needs to subscribe, because a

single Ancestry user can manage any number of DNA tests.

For

more about the Ancestry DNA test see my DNA

Masterclass – it’s an essential guide whether you are considering testing

or have already done so.

Save on Ancestry DNA US ONLY

Sunday

14th May is Mother’s Day in the US, which provides Ancestry with an

excuse to offer discount DNA tests.

Of

course, you don’t need to be a mother – or even female – to take an autosomal

DNA test, and when you order DNA tests from Ancestry you don’t have to decide

in advance who is going to be testing. I always aim to have a spare kit on hand

so that if the opportunity arises I can send it out to

my cousin immediately.

Ancestry.com

(US only) – save up to 30% on Ancestry DNA ENDS 14TH MAY

I’m

not currently aware of discount offers in other territories but please use the

links below rather than any that you might find in earlier newsletters, as those

older links may not work at all.

Ancestry.co.uk

(UK & Ireland) – Ancestry DNA

Ancestry.com.au

(Australia & New Zealand) – Ancestry DNA

Ancestry.ca

(Canada) – Ancestry DNA

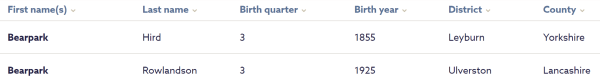

The right Bearpark?

Earlier

in this newsletter we were discussing the GRO birth indexes – and whenever I come

across a name that intrigues me I can’t resist search

the birth indexes to see how rare it is.

For

example, I came across the forename ‘Bearpark’ in the

census, and assumed it must be a mistranscription by

the enumerator; however there are two examples in the

birth indexes:

There are even

more births where ‘Bearpark’ was a middle name, so I

realised that it must have originated as a surname. It’s one of the rarer

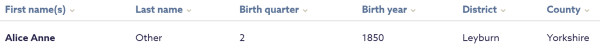

surnames I’ve encountered, but not nearly as rare as ‘Other’.

Disappointingly

I couldn’t find anyone whose initials were A.N. (ie A.N. Other). But I did find this birth:

She

might perhaps have been known as A. Anne Other, which sounds a bit like A. N.

Other.

Returning

to Bearpark, I searched the death indexes, and was

surprised to discover that although Bearpark Hird and Bearpark Rowlandson were

born 70 years apart, they both died in the same year, and in the same registration

district!

Even

though they were clearly related (the birth index shows that the maiden name of

the mother of Bearpark Rowlandson was Hird), it’s still a remarkable coincidence, albeit a sad

one.

I

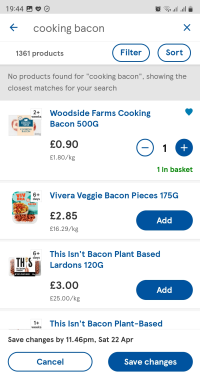

thought you might be amused to see these search results from the Tesco

groceries app . We hear so much

about the wonders of artificial intelligence these days that it’s sobering to

see how unintelligent computers can be when they really try!

. We hear so much

about the wonders of artificial intelligence these days that it’s sobering to

see how unintelligent computers can be when they really try!

Those

packs of cooking bacon frequently feature in my grocery basket – even though

the price has gone up from 55p to 90p over the past couple of years it’s still the

cheapest meat I can buy. I know that processed meats are thought to be unhealthy,

but bacon is so tasty that a small amount goes a long way.

Incidentally,

the carbon pawprint of pork is about a quarter of that for beef according to

this chart

on the Energy Saving Trust website. I discovered years ago that casseroles work

just as well when pork is substituted for beef, since the meat takes up the

flavour of the sauce. And it’s certainly a lot cheaper!

Staying

with Tesco, I’ve just noticed that they have slashed the price of Pimms from £22 for a litre bottle to just £10 for Clubcard holders (which is

£5 less than I paid less than a week ago, and £6.50 less than the price of the

smaller 70cl bottle!). This discount supposedly lasts until 8th May,

but I doubt that stocks will last that long, particularly now the sun has come

out, so it could be worth making a special trip to your local supermarket.

Finally,

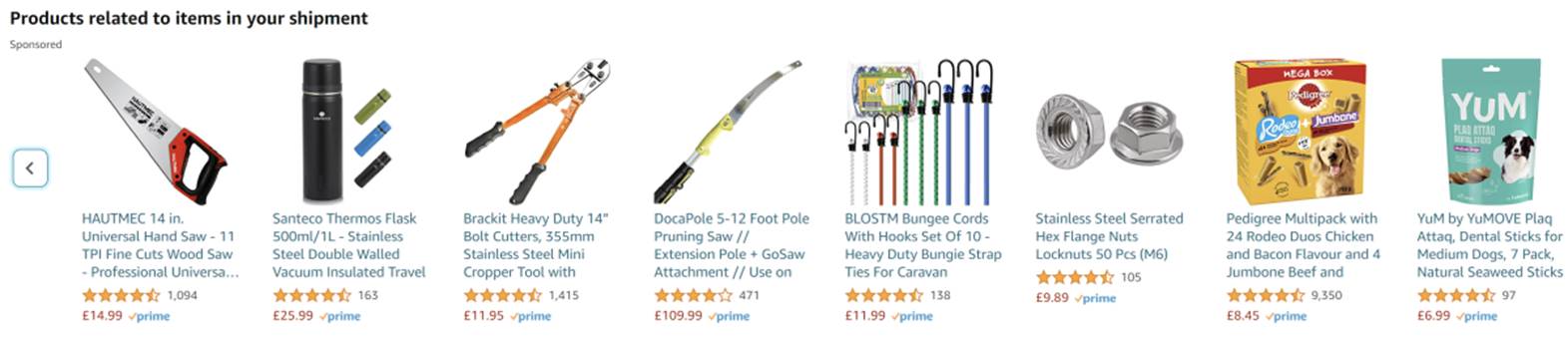

another example of artificial (un)intelligence, this time from Amazon:

My

order was for a pair of wire-cutters – we’re putting up wire fencing to protect

the plants in our garden from rabbits – so some of the suggestions make sense,

but how on earth did they come up with the items on the right? Do they somehow

know about the rabbits, and are hinting that we should get a dog?

This is where any major updates and corrections will be

highlighted - if you think you've spotted an error first reload the newsletter

(press Ctrl-F5) then

check again before writing to me, in case someone else has beaten you to

it......

I’ll be back soon, but in the meantime please remember that from

Monday 1st May until Tuesday 9th May we’ll be celebrating

the 19th Birthday of LostCousins and the Coronation of King Charles

III with TOTALLY FREE access to LostCousins – it’s a great chance to find the

cousins you’ve never heard of, but who share your interest in genealogy.

Peter Calver

Founder, LostCousins

© Copyright 2023 Peter Calver

Please do NOT copy or republish any part of this newsletter without permission - which is only granted in the most exceptional circumstances. However, you MAY link to this newsletter or any article in it without asking for permission - though why not invite other family historians to join LostCousins instead, since standard membership (which includes the newsletter), is FREE?

Many of

the links in this newsletter and elsewhere on the website are affiliate links –

if you make a purchase after clicking a link you may be supporting LostCousins

(though this depends on your choice of browser, the settings in your browser,

and any browser extensions that are installed). Thanks for your support!